Three new grower directors appointed to FAR board

Effective from 1 January 2026, there will be three new grower directors on the board of the Foundation for Arable Research (FAR).

FAR senior field officer Ben Harvey on the FAR research station at Chertsey in Mid-Canterbury. The paddock is a cover crop of buckwheat. Photo Credit: Nigel Malthus

FAR senior field officer Ben Harvey on the FAR research station at Chertsey in Mid-Canterbury. The paddock is a cover crop of buckwheat. Photo Credit: Nigel Malthus

A five-year randomised survey of herbicide resistance on New Zealand arable farms has found widespread high levels of resistance - with 71% of farms affected in the worst-hit region - South Canterbury.

"It's at higher levels than we thought," said Foundation for Arable Research (FAR) senior field officer Ben Harvey.

The survey, conducted in association with AgResearch, is the country's first national benchmarking of the problem of herbicide resistance. Going region by region over all New Zealand's major arable farming areas, farms were chosen at random from the FAR database. Weed seeds were collected from them, then germinated and grown, before being sprayed with a variety of herbicides, in a series of pot tests.

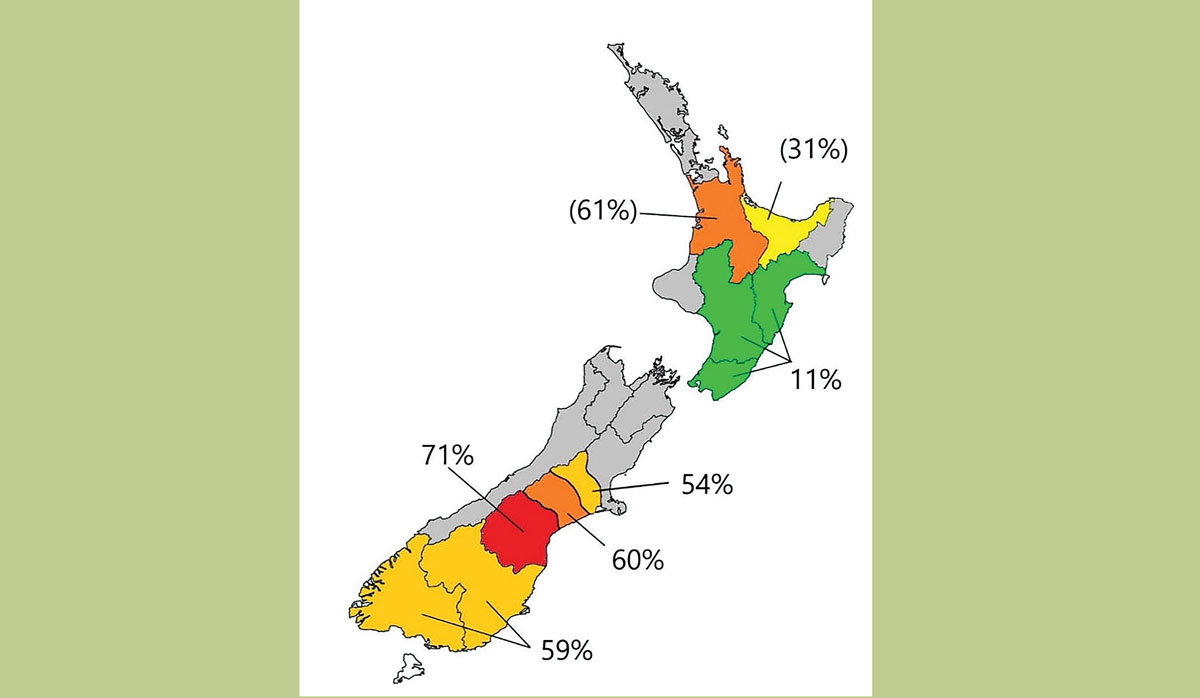

In South Canterbury, 71% of farms (22 out of 31) recorded at least one instance of a herbicide-resistant weed. By contrast, herbicide-resistant weeds were found on only 11% of farms in the southern North Island.

Harvey said the most common type of resistance found was grass weeds, mostly ryegrasses, resistant to the sulfonyl-urea group of herbicides.

These are the Mode-of-Action Group 2 herbicides - acetolactate synthase inhibitors such as iodosulfuron and chlorsulfuron.

The only other resistance detected was to Mode-of-Action Group 1 herbicides (Acetyl CoA carboxylase inhibitors such as haloxyfop and pinoxaden).

Group 1 herbicides are used to control grass weeds in a range of broadleaf and cereal crops. Group 2 herbicides have activity on a wide range of grass and broadleaf weeds and are also used widely in cereals.

FAR says the differences between regions are suspected to be due to differences in farming systems, with areas where crop rotation options are limited tending to have higher levels of resistance.

Other factors leading to differences in the regions may include:

Harvey told Rural News that South Canterbury arable farmers have quite limited options for rotation, largely because of their climate.

They generally tend to grow grass seed, cereals and oilseed rape. Some do a lot of wheat because it's the most profitable, he said.

"If you're growing continuous wheat, which is getting a lot rarer than it used to be, thankfully, then you're just using the same herbicide over and over and over."

Harvey said that any bag of ryegrass seed would contain some individual seeds naturally carrying the genes for resistance to sulfonyl-ureas.

|

|---|

|

Map showing the percentage of farms where at least one herbicideresistant weed was found during random surveys between 2019 and 2023. Supplied |

When a paddock used to produce ryegrass seed was then used for another crop in subsequent rotations, ryegrass would appear as a weed - including a few plants carrying the resistance.

"And if you spray them all off with this herbicide, the ones that are resistant will survive. They'll set seed, then the next year there'll be 100 of them, where there was only 10 before, then the next year a thousand, and exponentially they come to dominate the weed profile.

"Continuously spraying with the same herbicide over and over again leads to these resistant populations just dominating the weed population."

Another factor is that South Canterbury farmers tend not to use spring sowings, which can disrupt weed lifecycles.

"If you're always sowing in autumn, which is what they do down there, then you get the same sort of weeds that like to germinate each year."

Rotation Crops

FAR recommended that farmers use a "robust" rotation with a lot of different types of crops.

"Last year, we plotted a trial area of linseed because that's a different kind of crop or break crop, which you can use different herbicides in.

"I haven't seen the results for that yet, but these are the sorts of things that we're talking to growers down there about ways that they can just stop doing the same old thing over and over every year."

It was also important to use full label rates.

"Don't do a half rate because if you do have any survivors, then they're more likely to be resistant.

"Don't just use one type of herbicide, or use a pre-emerge and a post-emerge."

Farmers should also investigate other types of weed control, such as integrated weed management.

Ben Harvey said the low levels of resistance found in the lower North Island was likely due to their long rotations, often with pasture in it. When a paddock is in pasture, grazing would mean the seeds are being eaten, and the farmer wouldn't be using the same herbicide on it as when trying to suppress grass weeds in a cereal crop.

"They just have a different kind of farming system up there, that doesn't rely on them being quite so intensive in the way that they do their weed control."

Harvey said it was hard to put a dollar cost on herbicide resistance because there were so many other factors, but uncontrolled weeds was the one thing that would affect yield the most in a typical year.

Some farmers trying to get on top of difficult weeds by spraying out the bad patches with glyphosate before harvest, cutting the crop for silage instead of harvesting the wheat, or using more expensive and varied herbicides.

"One of the things that we're recommending is that they don't just use one herbicide, use a sequence or a mixture that are all of different kinds."

The 5+ A Day Charitable Trust has launched a collection of affordable recipes designed to turn everyday vegetables into seasonal stars.

Jane Mellsopp has been confirmed as the new Government Appointee to the New Zealand Meat Board (NZMB).

To celebrate the tenth anniversary of its annual Good Deeds competition, Rabobank will give away $100,000 to improve rural community hubs, schools, clubrooms, and marae across New Zealand.

Agricultural and veterinary product supplier Shoof International has appointed Michaela Dumper as its new chief executive.

Federated Farmers is celebrating following the Government's announcement that young farmers will be able to use their KiwiSaver funds to buy their first home or farm.

The Meat Industry Association of New Zealand (MIA) today announced that Chief Executive Officer Sirma Karapeeva has resigned from the role.

OPINION: A mate of yours truly reckons rural Manawatu families are the latest to suffer under what he calls the…

OPINION: If old Winston Peters thinks building trade relations with new nations, such as India, isn't a necessary investment in…