Farmers need to change their thinking about the value of spreading fertiliser on the hill country, an expert in the field claims.

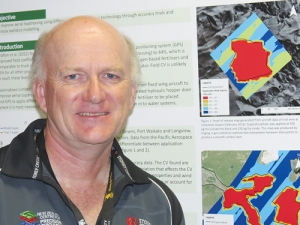

Ian Yule – professor of precision agriculture at Massey University— doesn't think farmers realise there is a huge difference between a good and bad spreading job. He says as long as they don't realise there is a difference – we are in a race to the bottom.

He says pilots have got million-dollar aircraft to maintain, but the ag aircraft fleet is getting older and operators are being forced to accept cheaper and cheaper prices for spreading fertiliser – making it harder for them survive. He believes farmers need to change their mind-set and focus on quality rather than cheap jobs.

According to Yule, the gains made in productivity in other areas of the primary sector haven't been made on the hill county. He believes this leaves the hill country more vulnerable and being locked into a low-income economic position

"Over the last 20 years a large number of farmers haven't been putting on enough fertiliser to get optimum productivity to just maintain productivity of their land," Yule explains. "The true picture is that we've reduced the stocking density on the hill.

"If you index the price over a period of say 20 or 40 years, then the prices we are getting for products are going down. So things are getting tougher and tougher for hill country farming." Yule says there is no short-term fix for the hill country and people need to think in terms of generations – rather than the next two or three years. He says things such as the scrutiny on nutrients and other environmental issues are additional pressures being faced by hill country farmers.

"I think there are various things we can do to improve the hill country and improving the spreading of fertiliser is one of them," he adds. "It's about being more accurate, avoiding areas that are more sensitive environmentally and paying greater attention to fertiliser loss.

"The whole topdressing industry got going 60 or 70 years ago because our hill country was slipping down the valley basically. We were getting a lot of soil erosion because soil fertility was dropping and they were desperate to do something about it; so there is certainly a base we need to reach in terms of protecting the land against erosion."

Yule says there are ways we can produce more from the hill country if fertiliser is applied more accurately. For example, on a typical dairy farm the best paddock may produce twice as much the worst paddock, but on the hill country the difference could be four or five times greater and reducing this gap is what needs to be done.

He says low incomes, high land prices, an increasing level of indebtedness and an emphasis on cash flows are some of the reasons why hill country farmers spend less money of fertiliser application. But Yule says with technology there is now ability to get greater efficiencies with topdressing.

"By incorporating technology we can avoid areas that are sensitive and improve the evenness of spread, because we have got control systems in the plane. One of the big things is than many people don't realise is that how variable the speed of the aircraft is," he explains.

"So we can to counter this electronically and adjust the opening of the hopper to achieve a more even application rate over a run. Currently, as a pilot does a run and his speed changes, very few have the capability to adjust the rate – that's not a criticism – it's just the fact that you are flying a low level aircraft in a pretty challenging environment; so there is limit as to what you can do."

Yule says with this technology it's possible to halve the coefficient variation or improve the accuracy of spreading. He says this particularly so on rolling country. Yule believes on this type of country a fixed-wing aircraft is the most competitive option – as opposed to the ground spreader.

"What tends to happen with using trucks over sloping land is that we've got bigger trucks that have got four-wheel-drive, twin axles and can go up gradients of between 10 and 20% -- so there is a risk of accidents because it is more dangerous. But also the spread path of the ground spreaders on those sorts of slope is actually far worse than an aircraft."

Yule says with auto GPS it's possible to calculate the speed of the aircraft and when this happens the settings on the hopper door can be changed instantaneously to get the right application rate.

He says the type of fertiliser is also important and with pelletised fertiliser it is possible to model its spread, but with finer fertiliser that is much more difficult.

"With the pelletised fertiliser for example if you have a boundary and you know you have got a little bit of wind say across that boundary you can adjust where you are going to fly your aircraft," Yule explains. "So you can get it in the right position and pretty-much predict where it should land from where it's released."

Most of the trials on the hill country have been done using fixed-wing aircraft and Yule says for larger jobs the aeroplane is probably the best option. But he'd like to do some tests to see how a helicopter would perform.