The tick will feed on all ruminants and has been reported on other animals and birds. As with all ectoparasites (parasites that live on the surface of the host), a heavy infestation can cause anaemia, considerable local skin irritation, some loss of body condition and, very occasionally, death (particularly in young animals).

In dairy cows, heavy tick infestations have been suggested to cause a reduction in milk production. Sheep with heavy tick infestations will rub due to irritation, reducing the quantity and quality of the wool clip.

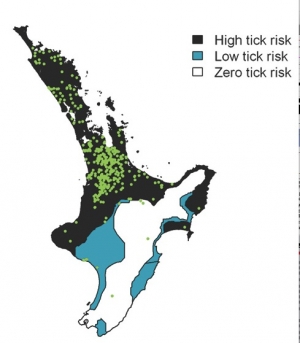

The tick is distributed in the warmer northern areas of New Zealand and has been recorded in Northland, Auckland, much of Waikato, Bay of Plenty, Gisborne and Taranaki. Distribution in the South Island is limited, with the tick present in Marlborough, Nelson and Takaka.

However, reports are limited by how close observations have been. The juvenile ticks, especially the larvae, are very small and therefore not obvious. Ticks feed where they can get access to blood vessels just under the skin surface, so small numbers are easily overlooked.

Tick activity

The cattle tick has four developmental stages: egg, six-legged larvae, eight-legged nymph and eight-legged adult. Generally, the tick completes one life cycle per year. However, in warm and moist conditions more than one life cycle may occur.

The New Zealand strain is parthenogenetic (reproduces asexually), so only adult female ticks are present.

Tick populations show a distinct seasonal pattern. Eggs are usually laid from late November to early February. These hatch into larvae after about 90 days. The larvae feed for up to seven days from late summer into the autumn. Fed larvae drop into the sward base and moult to become nymphs.

Nymphs first appear in late autumn and into winter. Unless the winter is very mild, nymphs have a period of dormancy and become active again in September and October. Adults first appear in early November, with their peak period of activity in late November to early January.

The tick spends most its life at the bottom of vegetation. Each stage, apart from the egg, must feed on blood from an animal host, but only once, before development into the next stage.

The period of time spent on the host animal is short – larvae feed for about seven days, and nymphs and adults for 5-14 days each. After feeding, the tick falls to the ground and develops into the next stage weeks or months later, depending on temperature. Unfed ticks can survive for up to 12 months.

When hungry, the larva, nymph or adult climbs up a plant stem to wait for a passing host. They sense the presence of a host by warmth, movement, change in light and carbon dioxide gradients. This is called ‘questing’. They grasp onto the host as it walks past, using their front legs. Once on the host, they seek softer skinned and better protected areas to start feeding, such as around the udder, under the tail and in the ears.

Tick behaviour is controlled by hunger and weather. Ticks do not like hot, dry conditions, being most active when the temperature is between 10-20oC and humidity is above 60%. Longevity is controlled by fat reserves and desiccation. In hot, dry conditions ticks have a short life if they do not encounter a host.

In cool and moist conditions, a tick will survive many months waiting for a host. Thus this tick is found in cold and snowy winter environments such as Hokkaido, Japan’s large northern island and home of their dairy industry, where winter snowfall can easily be one metre deep.