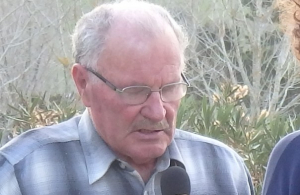

Gordon Levet of Kikitangeo Romney Stud, near Wellsford, believes sheep numbers will continue to drop. He says while the wool price went up last year, it has dropped about $2/kg in the last six months.

“We were getting $5/kg 30 years ago,” he told Rural News. “Now we are averaging $2.50/kg. I have just shorn my sheep and paid the shearer $10,000 and I don’t know how much I am going to get that will cover the shearing – $15,000-$18,000 if I am lucky.

“The cost of shearing the lambs is greater than the value of the wool because they don’t have a lot of wool on them – but you’ve still got to shear them.

“The lamb price is half what it should be. Federated Farmers said at least five years ago that to be economic it needs to be $150 a lamb. Prime lambs are probably making $80-$90, but there are a lot of store lambs that sold that between $40-$60.”

Levet says he’d heard of one lot of lambs sold locally that made $17. They were small lambs, but quite healthy.

“Sheep farmers don’t complain,” he says.

“They realise it is their choice to be farmers and they know they have got to accept what the world pays them. One of the problems with the wool farming is they can’t pass their costs on.”

Successive governments have brought in all sorts of new regulations which add costs to farmers – directly or indirectly, he says.

He has heard of other small rural businesses talking of having to close their doors because of compliance costs up to three figures with new health and safety regulations, despite never having had a problem in that area.

“You don’t hear a lot about this, but it is going on,” he says.

“I question how it stacks up from a cost benefit point of view. I have grave doubts as to whether it does stack up.”

New regulations need to take into account the economics of the proposals.

People are employed to visit every farm and inspect what they are doing.

“It has probably cost me a couple of hundred thousand already to bring in experts and tell me what I have got to do. I just wonder how much what they are doing will reduce accidents.”

But there’s no quick fix with the whole problem of the sheep industry, he says.

Levet says he’s heard that 100,000 bales have not been sold and China hasn’t used the lambs’ wool it bought last year.

“It is not going to clear very quickly. It took years to build up to a reasonable price and we lose it all in six months.”

In the longer term, Levet says lamb meat will be a niche market and there are plenty of wealthy people in the world who will pay a premium for it.

So he hopes the low lamb prices may just be short term.