Rippon: Personal, Sustainable Wine Experiences Redefined

In 2019, Rippon restructured its Wānaka cellar door, shifting from walk-ins to appointment-only tastings, capped at six guests per half hour.

As the second youngest of six kids, and the fourth generation on the land, Rippon's Nick Mills talks of his family's connection to a "ridiculously special place".

A long time ago, right around here, a big block of rock was pushed up out of the ocean. From time to time it got properly cold back then, so thick rivers of ice carved out deep valleys, leaving high mountains and a series of sheltered inland areas. A few hard, compressed lumps of bedrock remained, sitting in the middle of the basins like giant sheep sleeping on the land.

Fifty kilometres southeast of Mount Aspiring, next to Lake Wānaka and the Clutha Mata-Au river, sits a hard piece of schist, a hill, that stuck around through the ice-ages and formed gentle north-facing slopes of glacial outwash and gravels.

Because of its isolation, the only things to come here early on either blew, flew, washed up or swam here. With no browsing land mammals, the plants wore their skeletons on the outside and their flesh and fruit on the inside. Whole new life forms came to be. When humans arrived, they used this place as a soft inland camp, a place of gardening, rest and education: Wānaka.

By the time our Anglo-Saxon ancestors arrived, migration, the 1836 Te Puoho raid, and the 1858 Waste Lands Act meant this land was open for European land prospecting.

We started out as Sargoods here. Back in 1830, Frederick James Sargood, an English draper, married Emma Rippon and, together with their five girls and only son, moved to Melbourne to set up a soft goods business servicing the Victorian goldrush. Their son, Frederick Thomas (FT) Sargood, continued to grow the business and, in 1868, bought 27 hectares of scrub and developed Rippon Lea, a large house and garden. FT and Marian (née Rolfe) brought up a large family at Rippon Lea and one of their sons, Percy, moved to the happening town of Dunedin, at the time experiencing its own goldrush, to continue the family business.

Percy attended viticulturist Romeo Bragato's lectures to the Dunedin Chamber of Commerce in 1895 so, even before he purchased Wānaka Station in 1912, understood the region's potential for vines. However, it would be roughly another 70 years until his grandson Rolfe (my Dad), and Rolfe's wife Lois (my Mum), would begin to realise this potential.

So, hi, I'm Nick, the second youngest of six kids, and part of the fourth generation on our farm. I feel I got lucky with this life. As if being alive and cognitive on this beautiful planet wasn't enough, I got to grow up in a loving, supportive family, connected to one ridiculously special place.

Early on, we lived in a cottage built under massive trees on the Wānaka Station homestead block (now Wānaka Station Park), with a playground of farm stables, implements sheds and, always, the lake.

|

|---|

|

Rolfe "Tink" Mills, believing, at Rippon Farm circa 1973. |

When Rolfe and Lois built the house and moved the family up to the West Block, naming it Rippon Farm, it was still possible to walk back into the centre of town completely over farmland. It was pretty cool. You could go along the lake, navigating the old stock fences out into the water and nod to the young willow tree growing out of an old jetty post. Alternatively, you could go straight over the top, past the water race and old mill wheel, through the larches and goat paddocks. Looking back, I guess nearly all that one could see by the 70s was less than 100 years old, but it felt already ancient.

Rolfie, a gentle, always interested, always thoughtful man, had been doing that walk all his life. Tink, as Dad was to his mates, wanted to know more. He did his thing. From the hill, he observed it, studied it, took climate data, dug holes, travelled, talked, tasted. An original stock of vine material, seemingly of everything he could find, was planted, sampled and tested. The successful cultivars, those that demonstrated they were comfy in the site, were then selected, cuttings taken and propagated through our own nursery - this became our school holidays as kids. The fields became vineyards, the goat shed was re-tapped into a winery, and the smell of mohair, much more slowly, wore off David's clothes and skin.

When we were at school, Wānaka looked really different to the place you see today. It was a service town to the high country-farming community. On the main street where the lakeside cafes are now, there was a tractor repair shop and a dairy. I think as a family we stood out a bit; we were goat farmers experimenting with wine, and Lolo was 25 years younger than her silver-haired husband and was always getting exotic things. She wasn't much good at meat and three veg: I still maintain that my sisters and I got to eat the first avocado in the Upper Clutha basin.

In the early 80s the garage filled up with multiple vintages of unlabelled, unbranded wine bottles. They got filthy and Dad kept on planting. We sold parts of the farm to raise capital for the next vineyard block or, more likely, to pay for the last couple. When the garage was full and the car demoted, Lolo bought trestle tables and a till. The goat shed, turned winery, also became a cellar and cellar door, and Rippon Farm, became Rippon Vineyard and Winery.

It's an odd model. It feels like many of my mates, dead and alive, fell in love with Burgundy and wanted to emulate that culture, that wine, somewhere else. Many of them have done this brilliantly. For us though, it was a longstanding relationship with a singular piece of land, first and foremost, and an adaptation or selection of the (viti)culture to that land. But it didn't take long for Pinot Noir to float to the top.

|

|---|

|

Nick Mills, also believing, at Rippon. |

In the early 90s I got to work in the vineyard and winery with Rudi Bauer when he was making some of the first seminal wines to come out of Central. I was in my final years at high school and I was quite into thinking. Rudi's a fan of Goethe and Thomas Mann; we clicked and I started to see what he did as a potential life choice for me. My parents, of course, were doing that too, but they were just my parents. Many of my siblings became winegrowers too and I feel like we all fell in love with the land first, deeply, and then sought educational experiences that would help us look after it better.

In Wānaka, we often hear the groan, "Oh it's not like it was when I first came here", but I think that that was probably always the case. Our late aunt Jill could remember the sound of the Clydesdales thundering over the paddocks, echoing off Roy's Peak, Mt Iron and around the valley. As bucolic as this image is, I wonder if the locals that were here before our family said, "well, there's goes the town!" I reckon there have always been people, flora and fauna feeling that way over the ages.

I think Vinifera though, at least as we know it, likes humans a bit more. We've co-existed for so long that we now feel at ease in the same places: mid-slope, facing the sun, security in elevation, protection from the mountains, dry feet, plenty of clean water. At Rippon, we hope that the emotions people feel when they see and feel our place can help them understand why our vines are so happy here. It is the vines' ungrafted, unirrigated, intimate and ongoing connection to this place that makes the wines what they are.

Feeling a human tie to a singular place is joyful. We're making compost, spreading biodynamic preps, restoring habitat, working in happy vines, making crazy wines, sharing them with people who care. I've also swum almost every shoreline and walked every skyline one can see from Rippon. I've had the pleasure of working most of my life alongside my wife, mother, two sisters and brother, not to mention a brilliant, loving, long-standing crew.

|

|---|

|

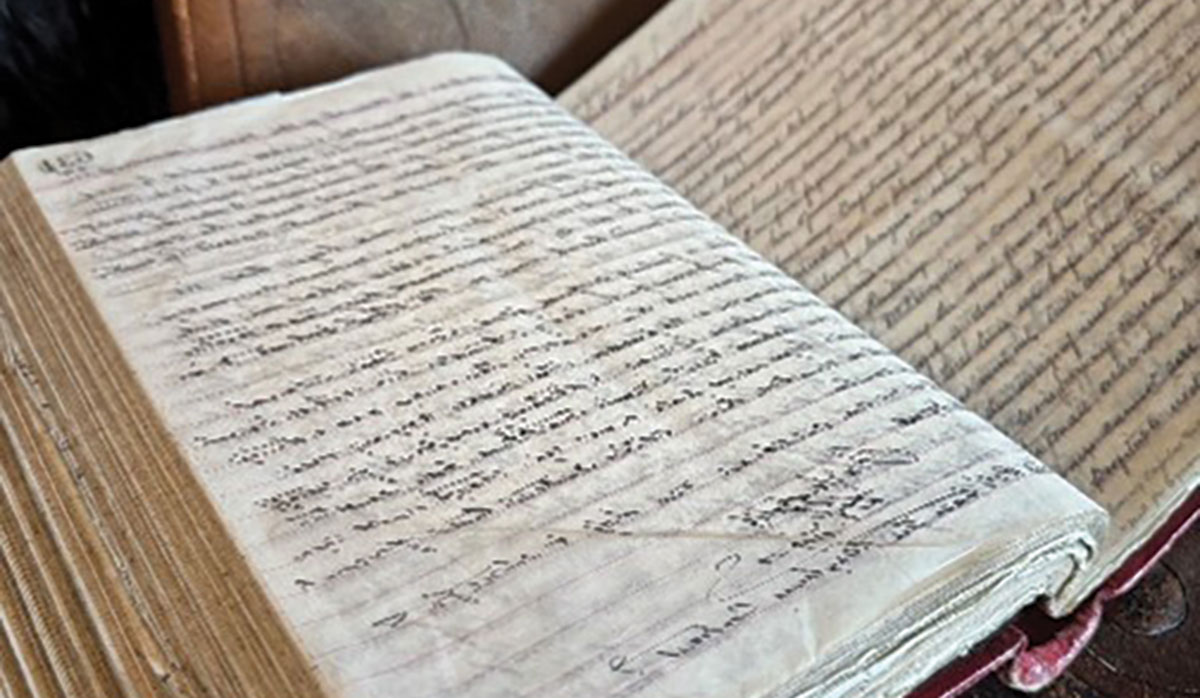

Percy's letter to his father FT Sargood, following Romeo Bragato's lecture to the Dunedin Chamber of Commerce in 1895, informing him of the viticultural potential in this "wonderous and faraway place". |

Maintaining the human connection is also our greatest challenge. It takes more than a back label to explain what we're about, as a brand. It's not always easy for the drinker to understand or care about their purchase decision having a direct impact on a piece of land somewhere. In Pinot Noir particularly, patience is a good thing. It takes a vine a long time to become part of its place. Likewise, human experience and olfactory memory can't simply be unplugged from one corporate being into another. Land and vines enduce past a single lifetime, so intergenerational knowledge is critical, yet farm succession is by far the hardest single agricultural activity to undertake. Its costs are measured in money and emotional health. Connection is tied to disconnection; surely the more we love something, the deeper we fear its loss.

These are scary, exciting times for winos. For better or worse, growing wine, for us, feels like the only way to stay here, but is that worth maintaining? For us? For our family? For the wine drinker? Do the customers benefit from this? I wonder sometimes if people see it as worth paying for. Maybe we could all just see farming as input in, result out, in a single lifetime. I hope not. I hope that the family, the people who work with us and the many who have done so in the past, feel it's worth it. Most of all, I hope that Rippon, the place, this beautiful individual, feels its value.

Sitting up there on the hill, the anabatic breeze coming off the lake, pushing over the crest, carrying it through everything - snowmelt, schist, wildflower - is almost inexpressible and certainly like nothing else I know. The sound still gets me to sleep at night.

Trade is important to our industry, whether it’s because 90% of our wine sales are in international markets, because of…

The end of the year is fast approaching, so here are some thoughts on a few of the significant developments…

Jimmy Stewart is quite literally chipping away at circularity.

A Wine Marlborough Lifetime Achievement Award is “very premature”, say Kevin and Kimberley Judd, nearly 43 years after they came…

Wine tourism has evolved into a sophisticated, diverse and resilient part of the New Zealand wine sector's economy. Emma Jenkins MW talks…