Central Otago Organics

Having 30% of Central Otago's vineyard area certified organic is "a true testament to the passion and dedication of growers", says Carolyn Murray, General Manager of the Central Otago Winegrowers Association.

At the recent Organic and Biodynamic Winegrowing Conference, Dr Charles Merfield from BHU Future Farming Centre, described nitrogen as “the joker in the pack” of 92 elements.

Why a joker? Because while it is all around us, very little of it can be used by plants.

While nitrogen makes up 80% of the atmosphere, plants can’t absorb it atmospherically. They can only absorb it via the soil.

“It can only get into a living thing through fixation by a very small number, literally a couple of handfuls, of bacteria and proteobacteria,” Merfield said.

In simple terms, atmospheric nitrogen is turned into reactive nitrogen within the soil by the above mentioned bacteria.

“The first form is ammonia and that is very quickly converted into ammonium. That is the really good form of nitrogen in the soil. It is available to plants to pick it up and it binds very tightly to the soil so it doesn’t leach.

“But ammonium is also then converted by bacteria into nitrites and nitrates.”

It is the nitrates that are the baddy in this equation of life for nitrogen. They do not bind to the soil and can be easily washed away, or leached out of the soil and end up in waterways – not a good thing whether you are an organic grower or not.

So how do you go about stabilising or increasing nitrogen to assist your vines. Given in organics you can’t use inorganic or imported nitrogen fertilizer, the options are foliar sprays, compost, or cover crops.

Compost first. While it is a renowned soil conditioner, Merfield warned compost is not the best source of nitrogen.

“The main nitrogen compound in living things is protein,” he said. “But protein only contains a small amount of nitrogen – about 6%. So it’s effectively impossible to have a biological organic fertilizer (such as compost) that contains more than 6% nitrogen. In total, compost provides only one or two percent total nitrogen and there is a shed load more potassium and phosphorus. So if you are using compost to supply nitrogen, you will be overdosing on P and K and a number of other nutrients as well. However it is a very good soil conditioner and has a number of other benefits.”

Foliar sprays.

Well these are extremely handy at the beginning of spring when nitrogen deficiency is likely to be at its highest. When you need to get something into the vines and see a quick reaction, foliar sprays are the simple answer.

“But foliar sprays are expensive and not all sprays are equal.”

Merfield suggested you may need to check research results to ensure you are getting what you want and ask for advice from someone who knows what they are talking about.

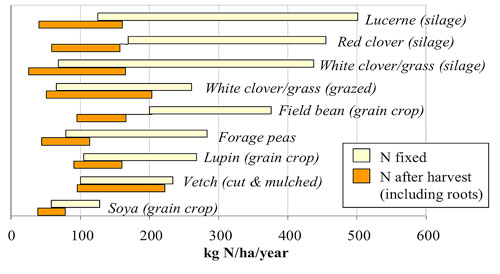

So if compost and foliar sprays don’t provide long-term answers, what other options are there? Creating your own nitrogen source through nitrogen fixing crops such as clover is one answer.

The best thing about crops is they can be removed before they create too much growth Merfield said.

“We can plant clover or other nitrogen fixing species for three or four months. That fixes enough nitrogen and then we can kill them off. So that way we have the ability to manipulate the amount of nitrogen we have in the vineyard. A bit like if you were applying it as a fertilizer – you can turn the taps on and off again.”

However there is a caveat here – and that is that you have to be careful of timing with cover crops. If the soil temperature is below about 8 Deg C, nitrogen fixing bacteria are inactive – it’s too cold for their chemistry to work.

“That means there is very little nitrogen fixing happening in the middle of winter. This is why we have nitrogen deficiency in spring, because the soil is cold from winter, yet the vines have their head in the warming atmosphere and are growing hard. However the bugs can’t operate to supply the nitrogen through the root system.”

Nitrogen catching crops are another way of building up the levels in your soil. These crops effectively grab the nitrates from the soil, before it leaches out from rain. Mustard or cereals are great catch crops Merfield said.

“But it is no use sowing these things when autumn is here, the soils are already draining. They need to be well established, so you need to be sowing them in summer so they have good solid roots on them when the water does start moving downwards, so they can grab the nitrates.”

Whether the best place to plant those crops is under the vine or inter row is something that requires a great deal more research Merfield suggested.

Undervine planting means nitrogen gets directly to where it is needed – the vine roots.

But there is always the issue of competition with the vines for water. How will you manage it when it comes time to remove, under vine cultivation? If so how will this affect the soil?

Inter row crops have less interaction with the vine roots, but they provide a low cost, easily maintained alternative. You can mow the crops easily, and even use the cuttings as a mulch if you can blow it back under the vines. Inter rows are also a good site to plant catch crops.

Regardless of which way you decide to go, Merfield warned there is no one crop fits all vineyard scenarios. He suggested that you trial any crop on a small part of your vineyard before taking it any further.

“Unfortunately the options and permutations are legion and often highly site specific, especially in viticulture. There is no one recipe for every vineyard.”

Jimmy Stewart is quite literally chipping away at circularity.

A Wine Marlborough Lifetime Achievement Award is “very premature”, say Kevin and Kimberley Judd, nearly 43 years after they came…

Wine tourism has evolved into a sophisticated, diverse and resilient part of the New Zealand wine sector's economy. Emma Jenkins MW talks…